Residual or Left over Spaces, are those spaces which are not considered while designing a city. They may consist of vast fields of unkempt grass, slopes where a wild flora has taken over, areas of bushes or fragments of nature. Maintenance is non-existent or cheapest possible – which explains a certain littering. Thus, they often display traces of spontaneous use: rests of huts, built by children or homeless people, remains of walks with dogs, lover’s meetings, and improvised picnics parties. Shortcuts, trodden diagonally between buildings, strips of medians, sparsely used parking lots and sometimes even sidewalks, connect significant places.

The poor physical state of these types of public spaces seems to rest with the fact that it is rarely clear who should be managing them after they are built, or after they have declined. As a consequence they are universally neglected. Hence they need to be recognized, avoided and defined during the initial designing process itself. The role of such spaces, needs to be identified, and an inquiry is needed on how all these factors can come together to result in well-designed, functional and meaningful open spaces, which can also make a positive contribution to improving the urban environment as a whole.

There are several reasons why residual areas are significant as settings for transgressive interaction and encounters: They provide transitions and intersections but also borders and barriers between sections or enclaves of the city. To pass them implies literally to cross a boundary. As fringe zones, they provide the exterior appearance, what we meet when leaving one enclave and entering another. As inter-mediate space, they may be experienced as belonging neither to this nor to that neighboring district. They represent land that is not subject to a complete and detailed order, but rather afford a certain freedom of action. As deserted or little-used land they are in frequently controlled by the owner. It is not always clear whose rules and norms that regulate their use. They offer places for activities that are excluded from the organized urban environment for being too space consuming, annoying or disturbing. They make possible unexpected encounters between people that act outside of their customary roles. They enable actions that escape the strict control of parents, teachers, neighbors and authorities. As fragments of nature or naturalized city they provide biotopes, some-times displaying an unexpected abundance of species.

Rob Kier defines urban space as ‘comprising all types of space between buildings in towns and their localities.’ Thus urban space is a fundamental part of the infrastructure of towns and cities; a resource which is much more all-inclusive than traditional view that it simply comprises a limited typology of distinct sites such as parks, sports grounds and city squares. Urban space is understood here to include all the non-built up land within and around urban areas, forming a matrix of space which connects inner urban areas with the surrounding landscape. But one of the problems with planning and architecture today is that the spaces between buildings are rarely designed. This is especially true in the case of this century’s modern movement - Stanford Anderson, On Streets.

Modern space is, in effect, anti-space; the traditional architecture of streets, squares and rooms created by differentiated figures of volumetric void is by definition obliterated by the presence of anti-space, which leads to the erosion and eventual loss of “space”, and the result of this can be seen all around us says Steve Peterson, Harvard Architectural Review

Although sometimes included in plans, they often constitute the indirect result of planned building and exist in the outmost periphery of architects and planners intentions. They often are simply perceived as exploitable land by urban renewal or densification projects, when new functions are to be added or when transportation networks are transformed or expanded. The process of making residual space useful may involve conflicts with users’ interests, unknown to the planners.

Important questions which are needed to be addressed:

What leads to the formation of these residual spaces?

What are the losses suffered due to formation of such spaces?

Why is there a need for these spaces to reduce and eventually fade?

How should we organize the planning process?

Concept of Residual Spaces:

Defining residual spaces:

Concept of Residual Spaces:

Cities are composed of many types of space, including that which exists between the built environment, wedges of spaces defined by the infrastructure of transportation, communication, industry and development. This includes what Jacobs refers to as the ‘Border vacuums’, what Trancik calls ‘urban anti-space’ or ‘Lost space’. This is the odd shape left over where highways cross, where a once active waterfront goes unused, where a stretch of land borders a campus or large complex, where railroad tracks have been abandoned, where a building has burned and the lot has gone into weeds. This may even be what Koolhaas calls ‘junk space’ after its final demise: empty shopping centres, obsolete car showrooms, abandoned stores or fast food restaurants, and their adjacent parking lots. While people can and do often use this residual space for a multitude of purposes, these are not thought of as public space.

When we think of urban public space, it is more often parks, plazas, malls, and squares that come to mind. Many of these programmed spaces have been created to be used in a certain way, at specific times, by certain types of people, for a limited set of purposes. But Residual space offers opportunities to withdraw from the formal and informal control of public space to a less controlled territory. Spaces which often appear as distances to cross when taking a bus, going to the shop, school or work.

The security ranges along highways and railroads, spaces that separate one housing estate from another, land reserved for future expansions; all are characterized by not directly being designed for a certain activity or set of activities. In that sense, residual areas are often unformed, formless or shapeless.

Danish architectural researcher Tom Nielsen promotes the term “surplus landscape” .Surplus landscapes, according to Nielsen, are phenomena that exist beyond what architects and planners normally define as their professional domain. Thus they are not the results of direct design processes, but rather secondary consequences of planning and building.

“The emptiness of place is in the eye of the beholder” (Bauman 2001, p.26 f) What Bauman refers to as empty spaces covers two categories that each has its own logic. One of them – the left-over spaces – is related to the forms and functions of built structure, and the other to complex and dynamic socio-cultural processes of the urban environment. Firstly, what Bauman describes as neglected, non-colonized and leftover places in a general sense, seem to describe some kind of residual space, public only in a broad sense of the word. Secondly, what Bauman refers to as empty spaces of the mental maps of different inhabitants, is a general condition of urban space – and also a precondition of residual space. Residual spaces may be parts of those regions that are prevented from being seen and experienced by some individuals and groups. Thus, the predicament of residual space – if we follow Bauman – is a dual emptiness.

Hence the domain of residual spaces is vast and varied so it is required to begin to approach residual areas – by sketching the scope and connotations of the term Residual space and, discovering that it has a history that is closely connected to modernist planning.

Defining residual spaces:

Residual spaces are defined as spaces of obsolescence; unproductive, dysfunctional, urban territories that do not any longer meet conventional, aesthetic and economic expectations. In the transitional zones between different built enclaves or in intermediate zones within such areas, people are moving, sometimes on planned walk paths, some-times following shortcuts. Unplanned or left-over land, may be saved as reserve plots or noise prevention zones, now and then with remains of old buildings, attract inhabitants of all ages, pursuing all sorts of activities. Others are repelled by the ugliness and dangers they perceive in such areas. It is primarily such surplus areas – in planning lingo often called residual space.

Processes or causes that led to Residual spaces:

“The erosion of urban space is an on-going process which has been with us for the last 50 years in the guise of a democratic process”-Rob Krier, Urban Space.

PUBLIC SPACE THROUGH HISTORY -Bacon, E. Design of Cities, New York: Penguin(1976)

Throughout the ancient Greek and the Roman till the starting of late medieval era spaces between the buildings have been found as residuals in certain cases.

PUBLIC SPACE THROUGH HISTORY -Bacon, E. Design of Cities, New York: Penguin(1976)

Throughout the ancient Greek and the Roman till the starting of late medieval era spaces between the buildings have been found as residuals in certain cases.

Throughout the ancient Greek and the Roman till the starting of late medieval era spaces between the buildings have been found as residuals in certain cases.

Later it was during modernism when the Modernist movement believed in Scientific, Rational, Objective, Standardize-able ideas. Concept of spaces was not attempted to confine spaces but to play there role in continuous spaces. Mono functional zoning of urban spaces resulted in “lonely crowds” and, Loss of Identity and Legibility.

Public spaces were considered as the left over spaces, between the tall buildings and the skyscrapers, without any public life, considered as negative spaces which led to the Erosion of public spaces. An entire landscape was formed according to the principles of modernist thought, a discourse or representation of space expressed in building. Many residential estates of the Million Program really constitute enclaves, separated by corridors of remaining “nature”. Thus, administrative regions and geographical distances makeup a reality that supports the idea of people’s everyday life taking place on “islands”. This emphasis upon separate neighborhood areas is to be questioned .The relations and connections between such enclaves standout as crucial for the lived reality of the new urban lands-cape.

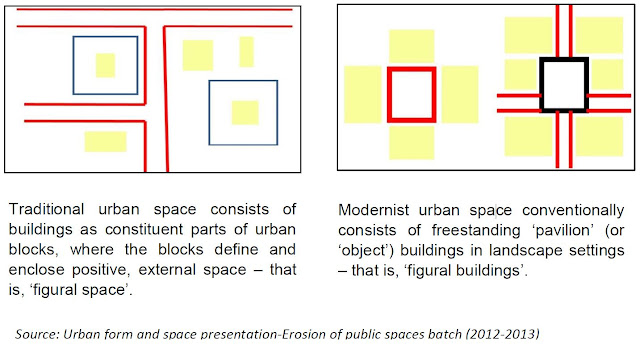

Traditional urban space v/s modernist urban space:

“Planning in the 17th and 18th century was concerned with total composition and organization (whether for utilitarian, aesthetic, iconic, defensive or as in most cases, a complex of such reasons). In the 19th century, as buildings became more utilitarian in their organization, the notion of function was gradually displaced from the external space to the organization of the internal space. A building tended to become in itself more of an object separate from its context” – Stanford Anderson, On Streets

Causes of Residual Spaces:

The major factors that have contributed to lost space in our cities as described by Trancik Roger, Finding Lost Space: Theories of Urban Design Development of the 20th century urban space-The Functionalist Program by Le Corbusier and Modern movement. An increased dependence on the automobile; Zoning and land-use policies of the urban-renewal period that divided the city; An unwillingness on the part of contemporary institutions —public and private—to assume responsibility for the public urban environment; and An abandonment of industrial, military, or transportation sites in the inner core of the city.

Classification:

In his paper Residual space and transgressive spatial practices, Tomas Wikström distinguishes between four rough types of residual space: Interzones, fringes, infrastructural border zones, and expansion areas. Each of them, it appears, relate to certain phases and varieties of production of space. Interzones are characteristic for modernist planning. They reflect the modernist principle of functional zoning. Interzones separate one unit of building from another, clearly emphasizing each part’s spatial independence. The interzones are primarily shaped by the form of the surrounding territories and provide buffers that tolerate irregularities of the edges of each built unit. Such zones surround and lie between different housing areas, around the large hospital area etc. In the interzones, well-trodden shortcuts run diagonally, effectively allowing passages between separate areas.

Fringe areas is a term for those parts of residual space that forms the border of each unit. Contrary to inter-zones, fringes have a long history, going back to the first human settlements. Whenever space is cleared for communal living, a fringe is established where ordered and cultivated land meets the wilderness. Where the subareas of a city turn towards large forests, fringe areas evolve, characterized by the expansion of everyday activities outside the housing area. Their shapes reflect the forms of boundaries between planned and unplanned land. Also, parts of interzones may have the character of fringes. In the fringe areas of a city, shady or secret activities are found.

Infrastructural border zones are areas generated by the traffic system, the electric power network and main water and sewage pipes. They may be understood against the back-ground of modern welfare society and its struggle to control the negative effects of industrial and infrastructural growth. Main transportation arteries like thorough-fares and railroads are surrounded by safety zones and noise-abatement zones, sometimes planted or containing rests of nature, sometimes covered with concrete tiles or gravel and more or less devoid of vegetation. Although such zones are often fenced in, they may provide arenas for activities, legitimate or illegal. Footpaths along and sometimes illegal and dangerous crossings, such zones clearly illustrate deficiencies of the existing urban structure.

Expansion areas, finally, are future building or infrastructure sites. In a more general manner, such areas are related to phases of expansion. The prerequisite, however, is a planning body of some sort, whether public or private, which has the power to set aside grounds for future building. Their character varies, from completely un-cleared or unkempt to well prepared for future building and provisionally used for parking or as storage-yards. When not surrounded by fences, they offer space for illegal dumping of garbage, old furniture and even car-wrecks.

Geographically speaking, these provisional categories are not mutually exclusive; rather they are often super-imposed upon each other. Fringe zones seem to be the most general phenomenon, forming “halos” around each unit of building. Interzones may be overlaid by fringe areas, infra-structural border zones and expansion areas.

Lefebvre encourages the inhabitants of urban society to fight for the restoration of the places of their cities to spaces for multiplicity, meetings, games and festivity. His work “The Production of Space” celebrates the urban grid: the streets, the squares and the parks of the “traditional “city.

But what about the vacant, little used and mostly unkempt fields, strips and slopes, that surround the hierarchical spatial schemata of modernist housing production?

However, what actually is going on seems to be another kind of appropriation. It involves people making use of the surrounding urban landscape for a wide range of purposes– with recreation, personal growth and daily logistics as the most evident. These more or less unplanned and unorganized activities can be interpreted as appropriation in a weak sense, a use of space that leaves abundant traces, but never creates reliable and defensible strongholds.

The destructive aspect of anti-space or urban visual order, and use, of cities is described by Jane Jacobs in Chapter14, The curse of Border Vacuums, in The death and Life of Great American Cities. The main idea put forth in this reading is how large single use sites within the urban fabric create dead zone of borders, which fracture neighborhoods and fragment the city. I read this book while simultaneously reading about suburban sprawl, and began to think about how a well-designed urban or town space feels to be in, as opposed to much of what actually exists. I was also reading about Robert Moses, and his many highway projects that fragment the city, and how Jane Jacobs organized against this trend.

She was also advocating for mixed use districts, an idea that was antithesis to suburbanization , which dictated that people live in one place, shop in another, work in another and recreate in still another. It was the development of large single-use structures and spaces that led to many of the anti-spaces and border zones.

Over the Past few years, radically changing economic, industrial, and employment patterns have further exacerbated the problem of lost space in the urban core. This is especially true along highways, railroad lined, and waterfronts, where major gaps disrupt the overall continuity of the city form. Pedestrian links between important destinations are often broken, and walking is frequently a disjointed, disorienting experience.- Trancik Roger, Finding Lost Space: Theories of Urban Design, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1986 (pg-2)

Over the Past few years, radically changing economic, industrial, and employment patterns have further exacerbated the problem of lost space in the urban core. This is especially true along highways, railroad lined, and waterfronts, where major gaps disrupt the overall continuity of the city form. Pedestrian links between important destinations are often broken, and walking is frequently a disjointed, disorienting experience.- Trancik Roger, Finding Lost Space: Theories of Urban Design, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1986 (pg-2)

It would be important also to explore to see how this issue manifests itself in European and Asian cities.

Urban landscapes in India are today emerging as a set of disparate conditions spreading across the country irrespective of the city boundaries. These conditions such as transportation facilities like the railways, road networks, flyovers and high ways form the basis of contemporary Indian urbanism. They mark the nature of city’s progress and observe the need of the public. However, there are vast amount of urban spaces which appear in various scales, intensities and forms which are abandoned due to such kind of urbanism.

Comments

Post a Comment